Close

Calls: We Were Closer to Nuclear Destruction than We Knew

Part 1

“The

proposition that nuclear weapons can be retained in perpetuity and never used —

accidentally or by decision — defies credibility”

This unanimous statement was published by the Canberra Commission in

1996. Among the commission members were internationally known former ministers

of defense and of foreign affairs and generals.

The nuclear-weapon states do not intend to abolish their nuclear

weapons. They promised to do so when they signed the Nuclear Non-Proliferation

Treaty (NPT) of 1970. Furthermore, the International Court in The Hague

concluded in its advisory opinion more than 20 years ago that these states were

obliged to negotiate and bring to a conclusion such negotiations on complete

nuclear disarmament. The nuclear-weapon states disregard this obligation. On

the contrary, they invest enormous sums in the modernization of these weapons

of global destruction.

It is difficult today to raise a strong opinion in the nuclear-weapon

states for nuclear disarmament. One reason is that the public sees the risk of

a nuclear war between these states as so unlikely that it can be disregarded.

It is then important to remind ourselves that we were for decades,

during the Cold War, threatened by extinction by nuclear war. We were not aware

at that time how close we were. In this article I will summarize some of the

best-known critical situations. Recently published evidence shows that the

danger was considerably greater than we knew at the time.

The risk today of a nuclear omnicide—killing all or almost all

humans—is probably smaller than during the Cold War, but the risk is even today

real and it may be rising. That is the reason I wish us to remind ourselves

again: as long as nuclear weapons exist we are in danger of extermination.

Nuclear weapons must be abolished before they abolish us.

Stanislav Petrov: The man who saved the world

1983 was probably the most dangerous year for mankind ever in history.

We were twice close to a nuclear war between the Soviet Union and the USA. But

we did not know that.

The situation between the USA and the Soviet Union was very dangerous.

In his notorious speech in March 1983, President Reagan spoke of the “Axis of

Evil” states in a way that seriously upset the Soviet leaders. The speech ended

the period of mutual cooperation, which had prevailed since the Cuba crisis.

In the Soviet Union many political and military leaders were convinced

that the USA would launch a nuclear attack. Peter Handberg, a Swedish

journalist, has reported of meetings with men who at that time watched over

sites where the intercontinental missiles were stored. These men strongly

believed that an American attack was imminent and they expected a launch order.

In Moscow, the leaders of the Communist party prepared for a counter

attack. The head of the KGB, the foreign intelligence agency, General Ileg

Kalunin, had ordered his agents in the world to watch for any sign of a large

attack on the Mother Country.

A previous head of the KGB, Jurij Andropov, was now leader of the

country. He was severely ill and was treated with chronic dialysis. He was the

man ultimately responsible for giving the order to fire the nuclear missiles.

The nuclear arms race was intense. The USA and the Soviet Union were

both arming the “European Theater” with medium-distance nuclear missiles.

President Reagan’s “Star Wars” program was a source of much anxiety on the

Russian side. The belief was that the USA was trying to obtain a first strike

capacity. In Russia, a Doomsday machine was planned—a system that would

automatically launch all strategic nuclear weapons if contact with the military

and political leaders of the country was completely disabled.

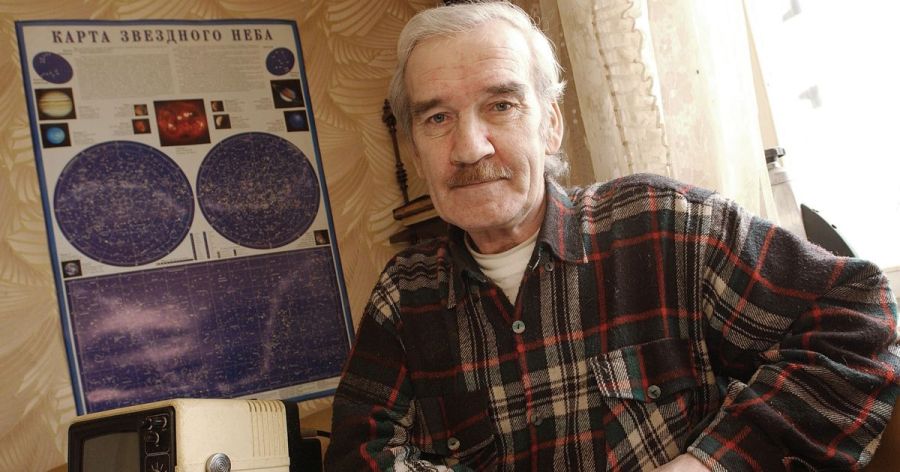

Stanislov Petrov

The increased risk of war was felt particularly strongly by those in

Russia who were ordered to prepare for an immediate response in case of a

nuclear attack. The command centre situated in the military city Serpukov-15

was the hub for the vigilance, evaluating reports from satellites in space and radar

stations at the borders. Colonel Stanislav Petrov was ordered to take the watch

on the evening of September 25, instead of a colleague who had called in sick.

Late in the evening, the alarm sounded. A missile had apparently been

fired from the American west coast. Soon two were detected; finally four. The

computer warned that the probability of an attack was at the highest level.

Petrov should now, according to the instructions, immediately report

that an American attack had been discovered. Against orders, he decided to

wait. He knew that if he reported a nuclear attack a global war would be

likely. The USA, the Soviet Union, and most of mankind would be exterminated.

Petrov waited for more information.

He found it very unlikely that the USA had launched only a few

missiles. Petrov was well informed about the computer system and he knew that

it was not perfect.

After a long wait the “missiles” disappeared from the screens. The

explanation came at last: There was a glitch in the computer system.

Petrov had himself been involved in developing the system. Maybe this

special knowledge saved us? Or unusual self-confidence and courage in an

unusual individual?

This fateful event became known when a superior officer, who had

criticized omissions in Petrov’s records of the evening, told the story on his

deathbed. Petrov has received rather little recognition in Russia.

What happened that critical night—and Petrov’s part in the story—is

played out in a recent movie by the Danish producer Peter Anthony: “The man who

saved the world.”

“Able Archer”: A NATO exercise which could have become the last

Just like the “Petrov incident,” the “Able Archer” crisis was

known only to a few military and political leaders in Russia and the USA until

decades later. Only in 2013 could the Nuclear Information Service get access to

the classified US file. Important documents from Russia and Great Britain are

still not available. Why do our leaders feel they need to “protect” us against

the truth of the greatest dangers mankind has faced?

Soviet SS-20 missile

“Able Archer” was a NATO exercise carried out in the beginning of

November 1983. The purpose was so simulate a Soviet invasion stopped by a

nuclear attack. About 40,000 soldiers participated and large troop movements

took place.

Similar exercises had been carried out in previous years. The

development could be monitored by Soviet intelligence through radio

eavesdropping. What was new was that the tension between Soviet and the USA was

stronger than before. In the background was the Soviet operation RYAN, an

acronym for an attack with nuclear missiles. RYAN had become the strategic plan

of the Soviet KGB two years earlier, on how to respond to an expected American

nuclear attack. The combination of Soviet paranoia and the rhetoric of

President Ronald Reagan did place the world in great danger.

Soviet leaders thought that this exercise could be a parallel to

Hitler’s Operation Barbarossa, the military maneuver that suddenly was turned

into a full-scale attack on the Soviet Union.

The Soviet leaders placed bomb planes on highest alert, with pilots in

place in the cockpits. Submarines carrying nuclear missiles were placed in

protected positions under the Arctic ice. Missiles of the SS-20 type were

readied.

NATO concluded the exercises after a few days, with an order to launch

nuclear weapons against the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe. No missiles were

fired, however, and the participants went back home.

After the exercise the British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher learnt

from the intelligence service how the NATO command had been ignorant of the

serious misunderstanding in Russia of the intention of this exercise. She

conferred with President Ronald Reagan. It is likely that this information,

together with his viewing of the film “The Day After,” caused the conversion of

the President which was expressed in his State of the Union message in 1984: “A

nuclear war cannot be won and must never be fought.” Reagan continued this process

up to the famous meeting in Reykjavik in 1986, when he and President Gorbachev

for a brief moment agreed to abolish all nuclear weapons before the end of the

century.

An interesting and most worrying rendition of how the exercises were

perceived in Russia is given in the documentary movie “1983: Brink of the

Apocalypse.” The story is based on documents that became available in 2013 and

on interviews with some of those who were active on both sides in the

situation. Two spies were important in convincing the leaders of KGB that no

attack was underway. One was a Russian spy in NATO headquarters who insisted to

the KGB that this was an exercise and not a preparation for an attack. The

other, a Russian spy in London, gave the same picture.

We can conclude that a lack of insight in the USA and in NATO into the

perceptions in the Soviet Union put the world in mortal danger. Did two spies

save the world?

A reflection of the danger associated with this NATO exercise plays out

in the recent German TV production “Deutschland.”

The Cuba crisis: More dangerous than we knew

Soviet nuclear weapons were placed in Cuba. Fidel Castro and Russia’s

generals intended to use them if the USA attacked. A Russian submarine that

came under attack carried a nuclear weapon. A nuclear attack on the US was

closer than we knew.

The development of this crisis has been described in several American

books. “Thirteen Days” by Robert Kennedy is the best known and has also been

made into a movie. As the story is so well known I will not repeat it here.

In the reports, we can experience how badly prepared the political and

military leadership were for such a situation, and how little these two groups

understood each other. The generals saw no alternatives other than doing

nothing or destroying Cuba with a full-scale nuclear attack. Robert Kennedy

wrote that he even feared a military coup!

The US side had little information about plans and evaluations in

Moscow. There was no direct communication between Kennedy and Khrushchev.

The final Russian answer to President Kennedy’s proposal was sent from

the Russian Embassy to Kennedy by a bicycle messenger! (The “Hot line” was

installed after—and because of—the Cuban Missile Crisis).

We know less about what went on in Moscow, but Khrushchev’s memoirs

give some information. It seems that the Russian generals were greatly worried

about the image and prestige of Russia. “If we give in to the US in this

situation how could our allies trust us in the future. How could the Chinese

have any respect for us?”

The world knew at the time that the crisis was very dangerous and that

a nuclear war was a real possibility. Decades later we know more. Thus, Cuban

President Fidel Castro, at a meeting many years later with US Secretary of

Defense McNamara, said that if the USA had attacked Cuba, Castro would have

demanded that Russian nuclear missiles be launched against the USA.

An American U-2 spy plane was shot down over Cuba during the crisis.

Only much later were we informed that another U-2 plane in the Arctic had

entered over Soviet territory, misled by the influence of the Northern Light!

US fighter planes were sent to protect the U-2 plane. These planes were

equipped with nuclear weapons for this mission. Why? Was it possible for the

lone pilot to launch these weapons?

We have also belatedly learned that four Russian submarines carrying

nuclear torpedoes were navigating close to Cuba. The commanders were instructed

to use their nuclear weapons if bombs seriously damaged their vessel. At least

one of the submarines was hit by charges that were intended as warnings, but

the commander did not know this. The captain believed his submarine was damaged

and he wanted to launch his nuclear torpedo. His deputy, Captain Vasilij

Alexandrovich Arkhipov, persuaded him to wait for an order from Moscow. No

connection was established but the submarine escaped. Arkhipov’s role has been

highlighted in a movie which, like the film about Petrov, is called “The man

who saved the world.”

What would have been the consequence had the nuclear torpedo hit the US

aircraft carrier that led the US operation?

Quite recently, reports have surfaced from the US base on Okinawa,

Japan. During the Cuba crisis the order came to prepare for a nuclear attack

against the Soviet Union. There was considerable confusion at the nuclear

command at the base. An increase in the alarm level from DefCon-2 to DefCon-1

was expected but never came.

A bizarre event, which could have been come from a novel by John le

Carré, was called “Penkovsky’s sighs.” Oleg Penkovsky was a double agent who

had given important information to the CIA—the US Central Intelligence

Agency—about the Soviet nuclear weapons in Cuba. He had been instructed to send

a coded message—three deep exhalations repeated twice—to his contact were he

informed that the Soviets intended to attack. This sighing message was sent

during the Cuba crisis to the CIA. The CIA contact, however, realized that

Penkovsky had been captured and tortured and the code had been extricated.

Other serious close calls

In November 1979, a recorded scenario describing a Russian nuclear

attack had been entered into the US warning system NORAD. The scenario was

perceived as a real full-scale Soviet attack. Nuclear missiles and bombers were

readied. After six minutes the mistake became obvious. After this incident new

security routines were introduced.

Despite these changed routines, less that one year later the mistake

was repeated—this time more persistent and dangerous. Zbigniew Brzezinski, the

US national security adviser, was called at three o´clock in the morning by a

general on duty. He was informed that 220 Soviet missiles were on their way

towards the USA. A moment later a new call came, saying that 2,200 missiles had

been launched. Brzezinski was about to call President Jimmy Carter when the

general called for a third time reporting that the alarm had been cancelled.

The mistake was caused by a malfunctioning computer chip. Several

similar false alarms have been reported, although they did not reach the

national command.

We have no reports from the Soviet Union similar to these computer

malfunctions. Maybe the Russians have less trust in their computers, just as

Colonel Petrov showed? However, there are many reports on serious accidents in

the manufacture and handling of nuclear weapons. I have received reliable

information from senior military officers in the Soviet Union regarding heavy

use of alcohol and drugs among the personnel that monitor the warning and

control systems, just as in the USA.

The story of the “Norwegian weather rocket” in 1995 is often presented

as a particularly dangerous incident. Russians satellites warned of a missile

on its way from Norway towards Russia. President Yeltsin was called in the

middle of the night; the “nuclear war laptop” was opened; and the president

discussed the situation with his staff. The “missile” turned out not to be

directed towards Russia.

I see this incident as an indication that when the relations between

the nuclear powers are good, then the risk of a misunderstanding is very small.

The Russians were not likely to expect an attack at that time.

Indian soldiers fire artillery in northernmost part of Kargil region.

Close calls have occurred not only between the two superpowers. India

and Pakistan are in a chronic but active conflict regarding Kashmir. At least

twice this engagement has threatened to expand into a nuclear war, namely at

the Kargil conflict in 1999 and after an attack on the Indian Parliament by

Pakistani terrorists in 2001. Both times, Pakistan readied nuclear weapons for

delivery. Pakistan has a doctrine of first use: If Indian military forces

transgress over the border to Pakistan, that country intends to use nuclear

weapons. Pakistan does not have a system with a “permissive link”, where a code

must be transmitted from the highest authority in order to make a launch of

nuclear weapons possible. Military commanders in Pakistan have the technical

ability to use nuclear weapons without the approval of the political leaders in

the country. India, with much stronger conventional forces, uses the permissive

link and has declared a “no first use” principle.

The available extensive reports from both these incidents show that the

communication between the political and the military leaders was highly

inadequate. Misunderstandings on very important matters occurred to an alarming

degree. During both conflicts between India and Pakistan, intervention by US

leaders was important in preventing escalation and a nuclear war.

We know little about close calls in the other nuclear-weapon states.

The UK prepared its nuclear weapons for use during the Cuba conflict. There

were important misunderstandings between military and political leaders during

that incident. Today all British nuclear weapons are based on submarines. The

missiles can, as a rule, be launched only after a delay of many hours. Mistakes

will thus be much less likely.

France, on the contrary, claims that it has parts of its nuclear

arsenal ready for immediate action, on order from the President. There are no

reports of close calls. There is no reason to label the collision between a

British and French nuclear-armed submarine in 2009 as a close call.

China has a “no first use” doctrine and probably does not have weapons

on hair-trigger alert, which decreases the risk of dangerous mistakes.

Why was there no nuclear war?

Eric Schlosser, author of the book “Command and Control,” told this

story: “An elderly physicist, who had taken part in the development of the

nuclear weapons, told me: ‘If anyone had said in 1945, after the bombing of

Nagasaki, that no other city in the world would be attacked with atomic

weapons, no one would have believed him. We expected more nuclear wars.’”

Yes, how come there was no more nuclear war?

In the nuclear-weapon states they say that deterrence was the reason.

MAD—“Mutual Assured Destruction”—saved us. Even if I attack first, the other

side will have sufficient weapons left to cause “unacceptable” damage to my

country. So I won’t do it.

Deterrence was important. In addition, the “nuclear winter” concept was

documented in the mid-1980s. The global climate consequences of a major nuclear

war would be so severe that the “winner” would starve to death. An attack would

be suicidal. Maybe this insight contributed to the decrease in nuclear arsenals

that started after 1985?

MAD cannot explain why nuclear weapons were not used in wars against

countries that did not have them. In the Korean war, General MacArthur wanted

to use nuclear weapons against the Chinese forces that came in on the North

Korean side but he was stopped by President Truman. During the Vietnam war many

voices in the USA demanded that nukes should be used. In the two wars against

Iraq the US administration threatened to use nuclear weapons if Iraq used

chemical weapons. Many Soviet military leaders wanted to use atomic bombs in

Afghanistan.

What held them back? Most important were moral and humanitarian

reasons. This was called the “Nuclear Threshold.” If the USA had used nuclear

weapons against North Vietnam the results would have been so terrible that the

US would have been a pariah country for decades. The domestic opinion in the US

would not have accepted the bombing. Furthermore, the radioactive fallout in

neighbouring countries, some of them allies to the US, would have been

unacceptable.

Are moral and humanitarian reasons a sufficient explanation why nukes

were never used? I do not know, but find no other.

Civil society organisations have been important in establishing a high

nuclear threshold. International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War

has been particularly important in this regard. IPPNW has persistently pointed

at the humanitarian consequences of nuclear weapons and warned that a global

nuclear war could end human civilisation and, maybe, exterminate mankind. The

opinion by the International Court in The Hague, that the use or threat of use

of nuclear weapons was generally prohibited, is also important.

The nuclear-weapon states do not intend to use nuclear weapons except

as deterrence against attack. Deterrence, however, works only if the enemy

believes that, in the end, I am prepared to use nuclear weapons. Both NATO and

Russia have doctrines that nukes can be used even if the other side has not

done so. In a conflict of great importance, a side that is much weaker and

maybe is in danger of being overrun is likely to threaten to use its atomic

weapons. If you threaten to use them you may in the end be forced to follow

through on your threat.

The close calls I have described in this article mean that mankind

could have been exterminated by mistake. Only decades after the events have we

been allowed to learn about these threats. It is likely that equally dangerous

close calls have occurred.

So why did these mistakes not lead to a nuclear war, when during the

Cold War the tension was so high and the superpowers seemed to have expected a

nuclear war to break out?

Let me tell of a close call I have experienced in my personal life. I

was driving on a highway, in the middle of the day, when I felt that the urge

to fall asleep, which sometimes befalls me, was about to overpower my

vigilance. There was no place to stop for a rest. After a minute I fell asleep.

The car veered against the partition in the middle of the road and its side was

torn up. My wife and I were unharmed.

But if there had been no banister? The traffic on the opposing side of

the road was heavy and there were lorries.

The nuclear close calls did not lead to a war. Those who study

accidents say that often there must be two and often three mistakes or failures

occurring simultaneously.

There have been a sufficient number of dangerous situations between the

USA and Russia that could have happened at almost the same time. Shortly before

the Able Archer exercise, a Korean passenger plane was shot down by Soviet

airplanes. But what if Soviet fighters had, by mistake, been attacked and shot

down over Europe? What if any of the American airplanes carrying nuclear

weapons had mistaken the order in the exercise for a real order to bomb Soviet

targets? In the Soviet Union bombers were on high alert, with pilots in the

cockpit, waiting for a US attack.

What if the fighters sent to protect the U-2 plane that had strayed

into Soviet territory in Siberia during the Cuba crisis had used the nuclear

missile they were carrying?

Eric Schlosser tells in his book about a great number of mistakes and

accidents in the handling of nuclear weapons in the USA. Bombs have fallen from

airplanes or crashed with the carrier. These accidents would not cause a

nuclear war, but a nuclear explosion during a tense international crisis when

something else also went wrong, such as the “Petrov Incident” mentioned

earlier, could have led to very dangerous mistakes. Terrorist attacks with

nuclear weapons simultaneous with a large cyber attack might start the final

war, if the political situation is strained.

Dr. Alan Philips guessed in a study from the year 2003 that the risk of

a nuclear war occurring during the Cold War was 40%. Maybe so. Or maybe 20%. Or

75%. But most definitely not zero—not close to zero.

Today the danger of a nuclear war between Russia and the USA is much

lower that during the Cold War. However, mistakes can happen. Dr. Bruce Blair,

who has been in the chain of command for nuclear weapons, insists that

unauthorized firing of nuclear missiles is possible. The protection is not

perfect. In general, the system for control and for launching is built to

function with great redundancy, whatever happens to the lines of command or to

the command centers. The controls against launches by mistake, equipment

failure, interception by hackers, technical malfunction, or human madness, seem

to have a lower priority. At least in the US, but there is no reason to believe

the situation in Russia to be more secure.

The tension between Russia and the USA is increasing. Threats of use of

nuclear weapons have, unbelievably, been heard.

But we have been lucky so far.

As I said in the beginning of this paper, quoting the Canberra

Commission: “The proposition that nuclear weapons can be retained in perpetuity

and never used — accidentally or by decision — defies credibility. The only

complete defence is the elimination of nuclear weapons and assurance that they

will never be produced again.”

/https://www.niagarafallsreview.ca/content/dam/thestar/news/canada/2021/09/25/huawei-executive-meng-wanzhou-receives-warm-welcome-upon-return-to-china/_1_meng_wanzhou_2.jpg)

![]()

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.